The 1970s was a decade defined by social change, cultural shifts, and cinematic innovation. While big blockbuster hits dominated the mainstream, a number of underrated films quietly emerged—works that pushed boundaries, explored complex characters, and captured the darker aspects of a tumultuous era. These films, ranging from gritty noir thrillers to raw portrayals of violence and disillusionment, often went unnoticed, overshadowed by more popular releases.

However, many of these hidden gems are just as daring, bold, and memorable as their more famous counterparts. In this article, we revisit some of the most overlooked films of the 1970s, ones that perhaps aren’t mentioned as frequently in mainstream society; highlighting the gritty, atmospheric, and uncompromising works that still deserve recognition today.

1. Klute (1971)

Donald Sutherland stars as John Klute, a small-town cop who travels to New York acting as a private detective, investigating the disappearance of a friend. As Klute navigates the seedy underworld of New York, his enquiries lead him to Jande Fonda’s Bree Daniels, a call girl who may hold the key to his friend’s disappearance.

Bree is vulnerable yet independent, a woman trying to escape the very life she’s created for herself whilst simultaneously being unable to do so; drawn back in by forces beyond her control. Fonda’s performance is arguably a career best, earning an Academy Award for her display of interwoven strength and fragility.

Klute offers a more nuanced view of sex workers than other films of the time, and Fonda’s Oscar is especially fatidic this year, when we’ve seen Mikey Madison win Best Actress for portraying a sex worker in Sean Baker’s Anora.

In a decade of massive social and political turmoil, director Alan J. Pakula mastered the art of translating national paranoia onto the big screen, his All the President’s Men (1976) being the defining Watergate era thriller. Klute might not be quite up there alongside Pakula’s Watergate masterpiece, but its voyeuristic aesthetic and unsettling mood, blending psychological drama with classic elements of a noir thriller, mean it’s still one of the finest thrillers of the seventies.

2. Fear Is the Key (1972)

Michael Tuchner’s little-known adaptation of Alistair Maclean’s source novel is a terrific piece of work. Barry Newman, fresh from 1971’s more celebrated Vanishing Point, stars as John Talbot; a man on the run after gunning down a police officer and leading the authorities on a quite fantastic car chase.

But all is not as it seems. After his arrest, Talbot engineers his own kidnapping, managing to land in the hands of a group of criminals potentially responsible for a plane crash that opens the film. Confused yet?

Fear Is the Key keeps its cards close, leaving the audience second guessing everything. We assume Talbot is a good guy, but every move he makes adds to the uncertainty, as does the film’s shifting alliances and double-crosses.

Newman is compelling in the lead role; his determination and cynicism making him an easy presence to root for. Roy Budd’s superb score adds energy to proceedings, injecting urgency even as the pace slows in the seconds half. It’s a welcome shift, the opening half is so frantic that the film benefits from the more measured build towards its conclusion. In many ways, Fear Is the Key feels like a feature length episode of Miami Vice set in Louisiana, and that’s a massive compliment.

3. Across 110th Street (1972)

Primarily known for being one of the key films in the Blaxploitation era of the seventies, Barry Shear’s excellent neo-noir toes the line between gangster pic and cop drama and ends up straddling both worlds with stark intensity.

At times grim, nasty, and apologetically violent, Shear’s film is a social commentary of the time and doesn’t sugar coat its bleak outlook. The plot begins with a robbery gone wrong, with three men stealing $300,000 from the mob and sparking a chain reaction that inevitably involves the police, and all kinds of bloodshed.

Yaphet Kotto (who, a year later would go on to star as the villain in Roger Moore’s first Bond outing, Live and Let Die) plays Lieutenant Pope, a young by-the-book Black officer who teams up with Anothony Quinn’s Captain Matelli, an old-school, corrupt and casually racist veteran, and the pair’s uneasy partnership adds to the film’s tension. Their dynamic drives the film, with Pope frequently biting his tongue at Matelli’s outdated, bigoted nonsense; but Matelli himself knows his time on the force is running out, and clings to whatever power he has left.

Shear shoots the streets of New York with an unrelenting grittiness; the streets are filthy, the violence is sudden and ugly, and every character has major flaws. The film’s biggest legacy might well be Bobby Womack’s title song, but it unfairly shadows a film that is brutal, bleak, and frequently brilliant.

4. The Seven-Ups (1973)

When you think of the best car chases put to screen, there are some that will instantly flock to your mind. Peter Yates’s Bullitt (1969), Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971) and To Live and Die in L.A (1985), and perhaps Paul Greengrass’s The Bourne Supremacy (2004).

But rarely does anyone mention Philp D’Antoni’s The Seven-Ups; which like The French Connection also stars Roy Scheider in a lead role. Here, Scheider plays Buddy Manucci, the leader of an off-the books NYPD unit that specialises in busting criminals who get at least seven years in prison, hence the film’s title.

Things get complicated for Buddy and his unit when someone starts kidnapping mobsters and ransoming them back, leading to a vicious game of cat and mouse between the cops, the mob, and some suitably dodgy middlemen. Richard Lynch deserves praise as Moon, one of the creepiest henchmen in seventies cinema, he barely utters a word and yet his dead-eyed stare is enough to send anyone running for cover.

The car chase is a metal-crunching pursuit through New York, culminating in spectacular fashion, a suitable ending for an action sequence which has you on the edge of your seat for its duration. But it’s not just the car chase that defines D’Antoni’s film; this is an edgy cop thriller that is forgotten in the wake of The French Connection’s enduring legacy and is well worth your time.

5. The Stone Killer (1973)

Perhaps one of Charles Bronson’s best films and yet surely one of his least well known, The Stone Killer is good enough to warrant comparisons with Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971). Michael Winner’s film shares plenty in common with the ‘poliziotteschi’ sub-genre of crime movies that were popular at the time in Italy, with Bronson’s cop Lou Torrey on the trail of a former mobster who has established a kill squad to settle a gangland score.

We know where we stand with Lou from minute one; he’s moved from New York to Los Angeles after a career-ending incident, only to find himself caught up in a violent conspiracy. A routine arrest leads him to uncover a truly wild scheme, Vietnam war veterans being recruited as assassins for a mass execution of old rival mobsters.

While it might be easy to dismiss Winner’s film as simply another hardened cop thriller that cashed in on the success of Dirty Harry, Bronson’s world-weary performance as Torrey really pulls you into the film which moves briskly and thrillingly, jumping between cities, crime scenes, car chases and stakeouts.

While not as polished as some of the decade’s great crime films, The Stone Killer doesn’t need to be; it has a mean, gritty energy that makes it stand out. Its release was sandwiched between another two Bronson films, The Mechanic (1972) and Death Wish (1974), both films that have garnered much larger praise and followings, approval that deserves to be equally supplied to The Stone Killer.

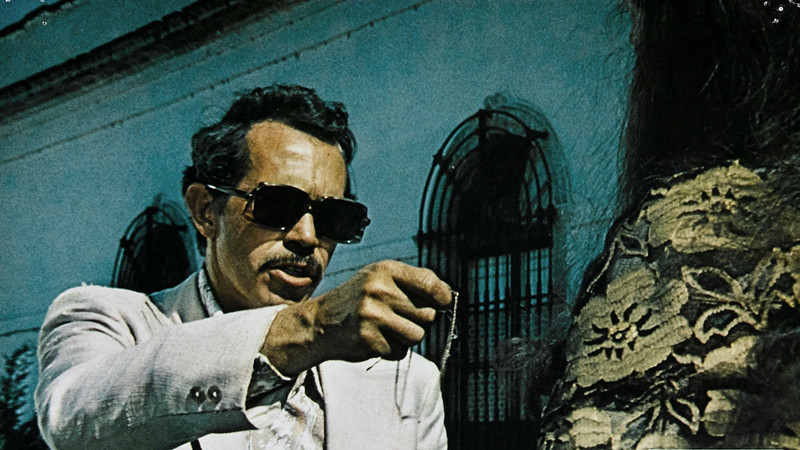

6. Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974)

Sam Peckinpah’s filmography is impressive to say the least. Not necessarily because it’s wall to wall masterpieces (it’s not) but because of the influence and controversy that sticks to some of them still to this day.

Straw Dogs (1971) remains one of the most contentious films ever made, and The Wild Bunch is still arguably the most violent western ever put to screen. Whether you agree with these sentiments or not, it’s undeniable that Peckinpah nearly always brings something interesting to proceedings. Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia is a nihilistic, dust-covered road movie that turns a straightforward bounty hunt into something far more unhinged. The film is drenched in sweat and tequila, and any happiness that is suggested at swiftly evaporates.

Warren Oats stars as Bennie, a washed-up piano player who scratches a living in a seedy Mexican bar, until he hears about a bounty placed on the head of Alfredo Garcia, and sets off with his girlfriend Elita (Isela Vega) in an attempt to find Garcia, on what quickly descends into a brutal and bloody trip filled with regret, desperation and violence. Oats is brilliant, channelling Peckinpah’s own sadly self-destructive tendencies (rumour has it that Peckinpah was in a period of alcoholic fear and trembling during production) as he drinks, stumbles and shoots his way through a filthy nightmare of a trip. The film feels lived-in and grotty for its duration, adding to the feeling of authenticity that Peckinpah brings to the film, leaning heavily into the dank and grimy ugliness of the story while the characters in it remain bitter and uncompromising.

Dismissed on release, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia deserves reassessment; it may well be Peckinpah’s most personal film, completely misunderstood on release as Peckinpah drank himself into an early grave.

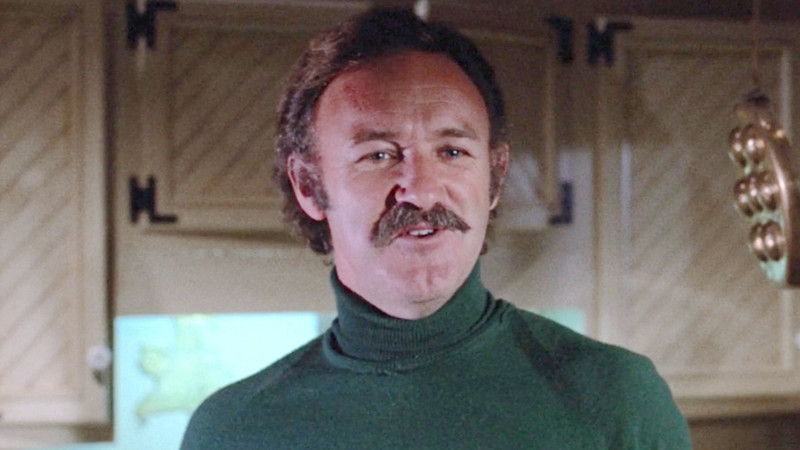

7. Night Moves (1975)

One of Gene Hackman’s finest ever films, Night Moves is sorely underseen and wildly underrated. Here, he plays moody private investigator Harry Moseby, hired by an ageing narcissistic actress to find her young daughter who has run away from home.

She is clearly a troubled lady but a narcissist nonetheless; far more interested in her own sex life (whilst being incredibly blasé about her sixteen-year-old daughter’s) than her daughter’s upbringing. Her only source of income is her daughter’s trust fund, and she spends that to hire Harry, knowing that the trust fund is reliant on her living with her daughter. Harry is also dealing with his wife’s infidelities, which is also part of the reason he takes the case; he simply doesn’t have the time to deal with their marital issues front on if he’s chasing a runaway across state lines.

The reasons that Night Moves is such an excellent film are manifold, the lead one being Hackman himself, channelling his inner “Popeye Doyle” from The French Connection (1975) to create a completely different character but one that is equally interesting to spend time with. Hundreds of films deal with characters who have their own personal demons but Night Moves combines both personal and career problems to make for a genuinely interesting set of characters; Harry’s wife isn’t just a throwaway female who’s cheating on him, she’s a fully rounded character whose issues come to the fore and eventually have to be addressed; meaning that when Harry is investigating the disappearance we feel the baggage he’s sitting on and don’t just forget about it.

It also helps that Night Moves has plenty of twists and turns and has you intrigued from the start, meaning you’re trying to join the dots yourself as Harry investigates, and the film’s screenplay adds to the excitement, leaving you with no clue how it’s all going to end.

8. The Man From Hong Kong (1975)

A truly mad romp, a film posing as an A-lister with a cast including former James Bond George Lazenby, this is an Ozploitation thriller that could almost be straight from the Grindhouse scene. Jimmy Wang Yu’s Hong Kong special branch agent is brought in by the Sydney police department to interrogate a drug mule, hoping the information garnered will lead to the man behind the trafficking itself, who may or may not be George Lazenby.

It’s hard not to think of the previous year’s Roger Moore fronted Bond film, The Man with the Golden Gun, and although on a technical level the Bond film is unsurprisingly superior, it’s hard to argue that this isn’t a whole heap more fun. It’s ridiculous almost beyond belief, but the choreography in the fight scenes is impressive; it’s insanely violent, and there are also clear influences on some of Tarantino’s work, especially the ‘Crazy 88’ fight in Kill Bill: Volume 1 (2003).

Directed by Brian Trenchard-Smith, The Man from Hong Kong is a wild mix of kung-fu action, seventies cop movie grit, and true chaos, enabling Lazenby to dial up the sleaze as crime boss Jack Wilton, relishing every moment as a man who’s as smooth as he is ruthless. It’s pure unfiltered seventies action, loud, fast, and gloriously over the top, a terrific B-movie that has enough in it to justify its posing as an A-lister, and it will have a smile on your face for all the right and wrong reasons.

9. Sorcerer (1977)

William Friedkin’s remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear (1953) was released just a month after Star Wars. Combine that with the fact that the budget of Friedkin’s film eventually rocketed to $22 million, it’s not hard to understand how and why the film died a death on its release in 1977. The shame of it, is that Sorcerer is a masterpiece.

The film follows four criminals; Roy Scheider’s American gangster, a hitman from France, a corrupt banker from Mexico, and a Palestinian terrorist who all end up stranded (for various reasons) in a godforsaken and lawless South American village, where no-one talks about their past, and there’s nothing to do but drink and contemplate your existence.

When a local oil company offers them a suicide mission, transporting highly unstable nitroglycerin across treacherous mountain terrain, with a big pay day for successful completion, the four men jump at the opportunity. What follows is a relentless exercise in tension, stripping everything down to pure survival; you can feel the exhaustion and hopelessness of the characters as well as being able to almost inhale the jungle as they precariously traverse the elements.

The infamous rope bridge scene is one of the most nerve-wracking sequences ever put to screen and somehow reminds you of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982) in a sadistic way, a film that was still five years away. It’s a relief to see that Sorcerer has had some sort of critical resurrection in recent years, but that doesn’t make up for the fact that it flopped on release. What it does do however, is enable many people who are yet to witness this astonishing piece of work a new lens to view it through.

10. Rolling Thunder (1977)

John Flynn’s Rolling Thunder (written by Paul Schrader) is one of the great revenge thrillers of the seventies, dark and brutal sure, but also strangely melancholic. William Devane is on career best from as Major Charles Rane, a Vietnam POW who returns home to a hero’s welcome but feels very out of place. He’s distant, haunted, barely present and struggling to make a connection with reality.

Things take an even bleaker turn when a gang of low-level thieves break into his house, murder his family and leave him for dead. What follows is a film that leans into the sub-genre of post-Vietnam disillusionment; something captured brilliantly for example in First Blood (1982) or latterly Dead Presidents (1995). But Rolling Thunder feels even more raw, released only two years after the end of the war and a year after Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), a film that Paul Schrader also penned).

Devane exudes a coldness that effectively assures us that he’s lost interest in life or indeed the consequences of his subsequent actions, and he’s not alone in his rampage of revenge; Tommy Lee Jones’s fellow disturbed vet is along for the ride, exuding a similar air of abandonment at his situation and fully understanding of Rane’s actions.

Rolling Thunder heavily influenced Bruce Springsteen’s 1978 album Darkness on the Edge of Town and was also cited by Quentin Tarantino as one of his favourite ten films of all time in a Sight & Sound poll; and it’s easy to see the impact of Flynn’s film on Tarantino’s work. The violence when it arrives, is vicious and unflinching, no glorification, just pure mean-spirited brutality, and a desolate reminder of Vietnam war reverberations.

Leave a Reply